How do we disseminate knowledge and make it accessible beyond the academic sphere?

University campuses are just one place where scholarship and learning happen, which means that we can turn to sites beyond the classroom to engage students and foster meaningful reflections. Last semester in my FREN 4813 special topics class, “In-Humanity: Cruelty/Literature/Media,” I invited students to visit a museum in Atlanta that aligned with the themes of our course. This exercise in experiential and kinesthetic learning allowed students to gain a deeper understanding of the questions with which we began the course: What is violence and what forms does it take? How do diverse modes of cultural production (literature, poetry, photography, film) respond to various types of violence and their aftermath? Complementing our in-class discussions that responded to assigned readings, films, and podcasts, the museum visit provided a different narrative mode and method through which to process and produce knowledge. This in turn both reinforced what was seen in class and, additionally, introduced students to other sources and their curation. I echo Isis Artze-Vega, Flower Darby, Bryan Dewsbury, and Mays Imad’s words, which draw on the correlation between student support and engagement: “Feeling safe, supported, and empowered, students are practicing democratic participation, engaging respectfully…on questions of sustainability, globalization, our shared history, and other issues that matter deeply to them” (The Norton Guide to Equity-Minded Teaching, 2022, p. 247). Through this “place-based epistemology: museums as sites of learning” activity, my hope was to encourage my students to take their profound reflections on the topics that matter deeply to them in a new direction while espousing the ethos of respectful inquiry and practice. The resulting testimonials speak to the power of the public humanities and civic engagement.

Writing about her experience visiting the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, Rachel Chin recounts the self-reflection that the museum stirred:

"I moved through the lower level, reading about the ordinary people who had to fight for their existence. I asked myself, “Could I have done this at the time?” Walking up the stairs from the replica balcony where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated into the Human Rights portion of the museum, I looked at the continued struggles for human rights and asked myself, “Why am I not doing something?” The museum made me realize that the struggles that happened in the 60s in America are not behind us at home or globally. My experience at the museum was moving and forced me to think of my role as a global citizen who can act locally."

Walking up the stairs from the replica balcony where Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated into the Human Rights portion of the museum, I looked at the continued struggles for human rights and asked myself, “Why am I not doing something?” The museum made me realize that the struggles that happened in the 60s in America are not behind us at home or globally. My experience at the museum was moving and forced me to think of my role as a global citizen who can act locally."

In my writing and teaching about violence, I always emphasize the fact that the study of conflict, upheaval, and injustice needs to be wholly interdisciplinary. In my work, I juxtapose policy documents to personal narratives, underscoring the importance of diversity of voice, mode, and medium when uncovering the details of both historical and contemporary cruelty. The ways in which history and experience are curated in museums echoes a methodology that privileges both institutional and personal narratives.

In her reflection on the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, Arleta Blake Underwood highlights the importance of these human stories:

In her reflection on the National Center for Civil and Human Rights, Arleta Blake Underwood highlights the importance of these human stories:

"The artifacts in the museum are much like the memoirs that we study in our class, giving us a window into an intimate, personal experience of fleeting moments in a heartbreaking/inspiring period of our history. Then, to expand on these feelings, there is the International Human Rights gallery, detailing the rhetoric of hate and racial violence in other parts of the world (some of which I was familiar with, some of which I was not). This section is emotional, drawing upon current issues as well as historical ones with interactive panels and multiple forms of media to explore. I very much enjoyed my tour of the National Center for Civil and Human Rights."

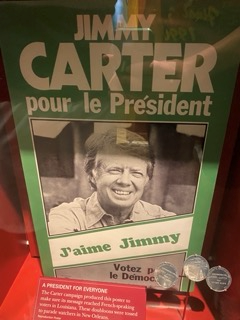

Studying the cultural, political, and social ramifications of global conflict is only half the battle, however. We must also think about what kinds of ethical solutions we can find moving forward. I grapple at length with the following question: How can we discern – even develop – an ethics of livability in today’s world? This query is at the heart of my “In-Humanity” course and at the core of creating sustainable communities. By living in line with the values of communities that prioritize in holistic ways the well-being of their members, we just might be able to reduce the types of violence that we see in various contexts globally. Like Rachel, Jack McGarity writes about the global citizenry that resonated with him during his visit to the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum, where he “learned about Jimmy Carter as a global humanitarian, both during his presidency and now in his later life.”

Dylan Gantt, who visited the Carter Library and Museum as well, also underscores the impact of social engagement:

"Going to the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum was a very engaging and rewarding experience, especially since it was the first presidential library I have ever been to. I enjoyed seeing Carter’s path to becoming a president from being a peanut farmer in rural Georgia and how his message of international peace spread so quickly throughout the country. I was also very intrigued by all of the international dilemmas and current events that occurred during his presidency, which were plentiful, and his incredible work creating a peace alliance between Israel and Egypt. The most impactful part of the exhibit for me was the last section of the museum, where all of his post-presidency work was showcased, including helping countries implement free and fair elections and providing better health and sanitation habits to many communities outside of the United States. This part of the exhibit really demonstrates how a single person can change the world for the better."

library I have ever been to. I enjoyed seeing Carter’s path to becoming a president from being a peanut farmer in rural Georgia and how his message of international peace spread so quickly throughout the country. I was also very intrigued by all of the international dilemmas and current events that occurred during his presidency, which were plentiful, and his incredible work creating a peace alliance between Israel and Egypt. The most impactful part of the exhibit for me was the last section of the museum, where all of his post-presidency work was showcased, including helping countries implement free and fair elections and providing better health and sanitation habits to many communities outside of the United States. This part of the exhibit really demonstrates how a single person can change the world for the better."

Thank you, sincerely, to Atlanta’s museums, to Serve-Learn-Sustain for democratizing access to these sites through a generous grant and, most importantly, to my FREN 4813 students for your robust discussions and nuanced insights all semester long!